Steroid-Induced Psychosis: How to Recognize and Treat It in an Emergency

Steroid-Induced Psychosis Treatment Calculator

Antipsychotic Dosing Guidance

Based on 2023 ACEP guidelines, steroid-induced psychosis requires 50-75% of standard antipsychotic doses. The American College of Emergency Physicians recommends:

- Olanzapine: 5-10 mg IM initially

- Haloperidol: 2-5 mg IM initially

- Risperidone: 0.5-2 mg IM initially

Recommended Dosing

Important: Always monitor for side effects and begin steroid tapering immediately. Symptoms typically resolve when steroid dose is reduced below 40 mg prednisone equivalent.

Critical Safety Note

Do not use standard antipsychotic doses for steroid-induced psychosis. The risk of dangerous side effects (cardiac arrhythmias, severe sedation) is significantly higher when using full schizophrenia doses.

When Steroids Trigger Psychosis: A Real Emergency

Imagine someone on high-dose steroids for a flare-up of lupus or severe asthma suddenly starts talking to people who aren’t there, believes they’re being watched, or becomes wildly agitated. It’s not a mental illness they’ve always had. It’s not drug abuse. It’s not delirium from infection. It’s steroid-induced psychosis - and it can happen fast, often within days of starting treatment. This isn’t rare. Around 6% of people on high-dose steroids develop severe psychiatric symptoms, and at doses over 80 mg of prednisone daily, that number jumps to nearly 1 in 5. Most emergency doctors don’t expect it. But if you’re prescribing or caring for someone on steroids, you need to.

How It Starts: The First Warning Signs

Steroid-induced psychosis doesn’t usually begin with full-blown hallucinations. It starts quietly. A patient who was calm and cooperative suddenly seems confused, restless, or overly emotional. They might stare blankly, repeat questions, or get angry over small things. These early signs - agitation, confusion, irritability - show up in the first 1 to 5 days after starting or increasing a steroid dose. That’s the window to act.

Studies tracking hundreds of patients show a clear pattern: the higher the steroid dose, the higher the risk. At 40 mg of prednisone per day, about 4.6% of patients develop psychiatric symptoms. At 80 mg or more, that rises to 18.4%. It’s not about how long you’ve been on steroids - it’s about how much you’re taking right now. Even short courses can trigger mania or psychosis. And it’s not just prednisone. Dexamethasone, methylprednisolone, and other synthetic corticosteroids carry the same risk.

What It Looks Like: Beyond the Myths

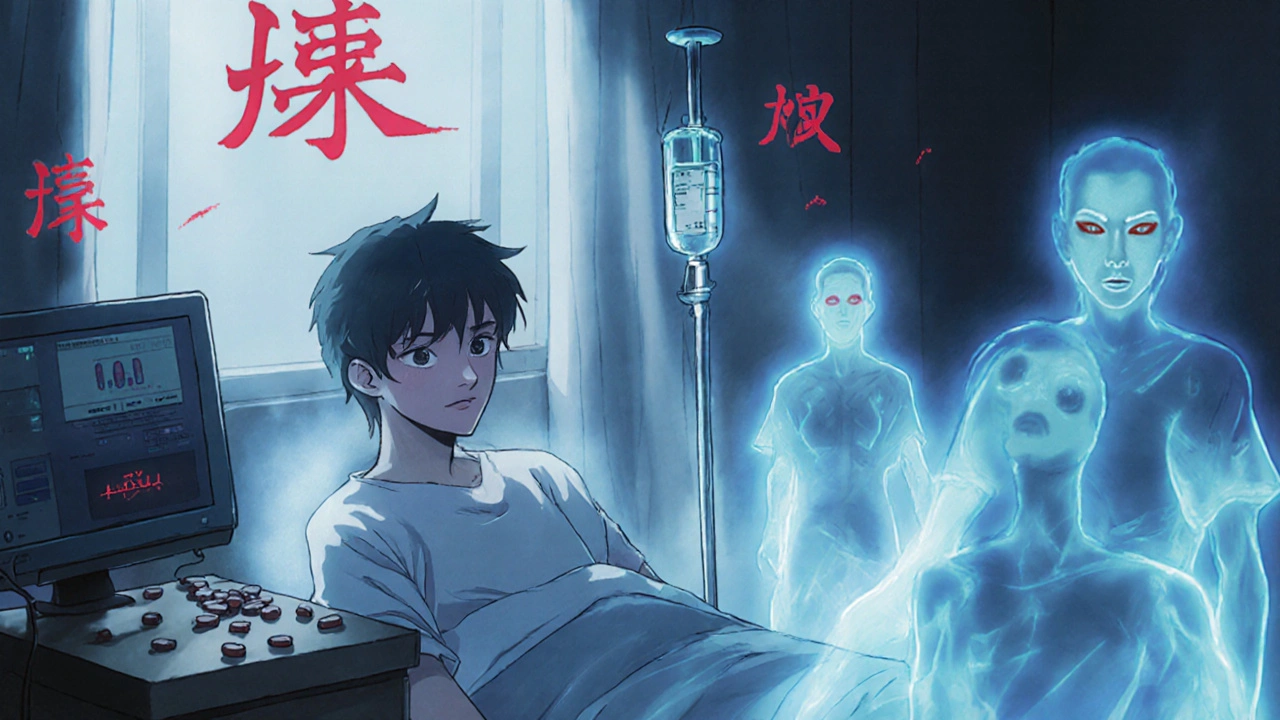

People assume psychosis means hearing voices and seeing ghosts. But steroid-induced psychosis often looks different. In one review of 79 cases, 40% had depression, 28% had mania, and only 14% had full-blown psychosis. Many patients aren’t hallucinating - they’re just deeply irritable, euphoric in a reckless way, or emotionally flat. Others have racing thoughts, sleeplessness, or grandiose beliefs - like thinking they can cure themselves or that they’re invincible.

What makes this dangerous is how easily it’s missed. A patient on steroids for COPD who starts yelling at nurses might be labeled as ‘difficult’ or ‘noncompliant.’ A teenager on high-dose steroids for nephrotic syndrome who stops sleeping and starts spending money recklessly might be thought of as ‘going through a phase.’ But if these changes happen after starting steroids, and no other cause fits, it’s likely steroid-induced. The DSM-5 says you must rule out everything else: infections, low sodium, high blood sugar, brain tumors, seizures, or other drugs before you can say it’s from steroids.

Why It Happens: The Brain on Steroids

Steroids aren’t just anti-inflammatory. They cross the blood-brain barrier and bind to receptors in areas that control mood, memory, and perception. High doses flood the system, disrupting the balance between glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors. This throws off the HPA axis - the body’s stress response system - and mimics what happens in Cushing’s syndrome, where the body makes too much cortisol naturally.

It’s not fully understood why some people are more vulnerable. But genetics likely play a role. Some people’s brains just react more strongly to synthetic cortisol. That’s why researchers at the NIH are now studying 500 patients on high-dose steroids to find genetic markers that predict who’s at risk. Until then, we treat everyone on high doses like they could be vulnerable.

Emergency Response: What to Do Right Now

If someone is agitated, aggressive, or clearly out of touch with reality after starting steroids, the first priority is safety - for them and everyone around them. Don’t wait. Don’t assume they’ll calm down. Don’t assume it’s ‘just behavior.’

- De-escalate first. Use calm, low tones. Remove crowds. Turn down lights. Offer water. Don’t corner them.

- Check for medical mimics. Order blood tests: glucose, sodium, potassium, calcium, liver and kidney function, CRP, and blood cultures. Hyperglycemia from steroids can worsen confusion. Infections like UTIs or pneumonia can trigger delirium that looks like psychosis.

- Confirm steroid exposure. What steroid? What dose? When did they start? Did they just increase it? Timing matters. Symptoms that begin within five days are far more likely to be steroid-related.

- Start treatment. If they’re too agitated to take pills, give IM olanzapine (5-10 mg) or IM haloperidol (2-5 mg). If using haloperidol, give diphenhydramine or benztropine to prevent stiff muscles or tremors. Avoid high doses - 20-30 mg of oral olanzapine is dangerous here. Stick to 2.5-20 mg total per day. Most patients improve in 2-7 days.

Physical restraints? Only if they’re trying to hurt themselves or others. Restraints can make psychosis worse. They’re not a treatment - they’re a last resort.

The Real Fix: Taper the Steroids

Medications help calm the symptoms, but they don’t fix the root cause. The only way to truly reverse steroid-induced psychosis is to lower the dose. In 92% of cases, symptoms fully resolve when steroids are reduced to below 40 mg of prednisone per day (or the equivalent in other steroids).

But here’s the catch: you can’t just stop steroids cold. If someone is on them for a life-threatening condition - like a transplant, severe autoimmune disease, or adrenal insufficiency - stopping abruptly can kill them. That’s why tapering has to be smart. Work with the prescribing specialist. Can you drop from 120 mg to 60 mg? Then to 40 mg? Then 20 mg? Do it over days, not hours. Monitor for withdrawal signs: fatigue, joint pain, nausea, low blood pressure.

If the underlying disease can’t be controlled without steroids, you may need to keep them on a low dose long-term - and manage the psychosis with ongoing antipsychotics. Olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol are the most studied. Lithium can help prevent mania, but it’s risky with kidney or thyroid issues. Antidepressants or seizure meds like valproate might help in some cases, but the evidence is weaker.

What Most Hospitals Get Wrong

A 2022 survey of 127 emergency doctors found that while 89% knew steroids could cause psychosis, only 43% followed the recommended tapering protocol. More than half gave antipsychotic doses meant for schizophrenia - double or triple what’s needed for steroid-induced cases. That’s not just unnecessary - it’s dangerous. High doses of haloperidol can cause dangerous heart rhythms. Too much olanzapine can cause sedation, low blood pressure, or even aspiration.

The American College of Emergency Physicians updated its guidelines in March 2023 to say this clearly: for medication-induced psychosis, use 50-75% of the usual antipsychotic dose. Start low. Go slow. Watch for side effects. And always, always try to reduce the steroid first.

What’s Coming Next

There’s hope on the horizon. The NIH study tracking 500 patients on high-dose steroids is expected to release its first data in late 2024. It’s looking for genetic markers - maybe a variant in the glucocorticoid receptor gene - that could tell doctors ahead of time who’s at highest risk. If you’re planning to start someone on 80 mg of prednisone, wouldn’t you want to know if they’re genetically prone to psychosis?

The American Psychiatric Association is also developing a clinical decision tool, due out in mid-2025, that will help emergency and primary care teams make faster, safer decisions. It will ask: What’s the steroid dose? How long have they been on it? Any prior mental health history? Any electrolyte issues? Then it will suggest: taper now? Start antipsychotic? Run these labs?

Bottom Line: Don’t Wait for the Worst

Steroid-induced psychosis is one of the most treatable forms of psychosis - if you catch it early. It’s not a psychiatric emergency. It’s a medical emergency. The fix isn’t more antipsychotics. It’s less steroids. And the sooner you act, the better the outcome.

If you’re prescribing steroids - especially above 40 mg/day - talk to your patient and their family. Warn them: ‘You might feel anxious, restless, or have trouble sleeping. If you start seeing or hearing things that aren’t real, or feel like you’re losing control, call us immediately.’

If you’re in the ER and someone shows up with sudden psychosis - check their meds. Ask: ‘Are they on steroids?’ If yes, don’t assume it’s schizophrenia. Don’t just give a high dose of haloperidol and send them home. Treat the cause. Taper the steroid. Give the right dose of antipsychotic. And save someone from months of unnecessary suffering.

Can steroid-induced psychosis happen with low doses?

Yes, but it’s rare. Most cases occur with doses above 40 mg of prednisone per day. However, some people are more sensitive - especially those with a personal or family history of mood disorders. Even 20 mg can trigger symptoms in vulnerable individuals. Don’t assume low dose means safe.

How long does steroid-induced psychosis last?

With proper treatment - tapering steroids and using low-dose antipsychotics - most people see improvement within 2 to 7 days. Full recovery usually happens within 2 to 6 weeks. If steroids aren’t reduced, symptoms can persist for months or become chronic. Early action is key.

Is steroid-induced psychosis the same as schizophrenia?

No. Schizophrenia is a chronic brain disorder with genetic and developmental roots. Steroid-induced psychosis is temporary and caused by a chemical imbalance from medication. The symptoms can look similar, but the cause, timeline, and treatment are completely different. If you reduce the steroid and symptoms go away, it wasn’t schizophrenia.

Can antidepressants help with steroid-induced depression?

Sometimes. If the main symptom is depression - not psychosis or mania - SSRIs like sertraline or escitalopram can help. But they’re not first-line. The priority is still reducing the steroid dose. Antidepressants may be added if depression persists after tapering, but they don’t fix the root cause.

What if the patient needs to stay on high-dose steroids?

If the underlying condition (like organ transplant rejection or severe vasculitis) requires ongoing high-dose steroids, then long-term antipsychotic treatment may be needed. Olanzapine or risperidone at low doses (e.g., 5 mg olanzapine daily) are often used. Close monitoring by a psychiatrist and the prescribing specialist is essential. Never stop life-saving steroids without a plan.

Man, this is gold. I work in ER and we see this all the time but never connect it to steroids. One guy thought he was Jesus and was trying to baptize the IV pole. Turns out he was on 100mg prednisone for a flare. We tapered him down and he woke up like, 'Wait, why am I in a hospital?'

This is so important. I'm a nurse and I've seen patients labeled 'difficult' or 'hysterical' when they were just chemically out of whack. The moment we check their meds and taper steroids, everything changes. No need for restraints, no need for high-dose antipsychotics. Just kindness, lower doses, and time. 🙏❤️

Of course it's steroids. Everything's steroids. Next you'll tell me the moon landing was faked by Big Pharma to sell antipsychotics. You know what really causes psychosis? The government's secret fluoride program. But hey, let's blame the steroid. Easy fix. Less responsibility. Classic.

Ohhhhh sweet mercy - imagine being a teenager on 80mg of methylprednisolone and suddenly thinking you’re a rockstar who can fly?! I once saw a kid try to jump off the ICU balcony screaming ‘I AM THE SUN!’ - and the nurse just said, ‘Honey, you’re on steroids.’ He looked at her like she’d just insulted his soul. Then he cried. Then he apologized. Then he asked for a snack. That’s the whole story right there.

Esteemed colleagues, the pathophysiological underpinnings of steroid-induced psychosis represent not merely a pharmacological anomaly, but a profound metaphysical rupture in the human neuroendocrine equilibrium. The synthetic glucocorticoid, in its arrogant ubiquity, usurps the sacred HPA axis - a temple of homeostasis - and replaces divine cortisol with the sterile tyranny of molecular mimicry. We are not treating psychosis. We are negotiating with a biochemical coup d'état.

Why are we even talking about this? Hospitals are run by idiots who don’t read the damn manual. If you’re giving 120mg of prednisone to someone with asthma, you deserve to get sued. And no, olanzapine isn’t the answer - the answer is ‘don’t prescribe so much.’ End of story.

Let’s be real - this is all a cover-up. The pharmaceutical industry doesn’t want you to know that steroids are just a gateway to deeper control. They use psychosis as a tool to normalize antipsychotics. The real solution? Quantum grounding. Or maybe just stop eating processed food. Also, I’ve been hearing voices since 2019 and they told me to comment on this. They’re very polite. 🌌👁️

So let me get this straight - you’re telling me a 16-year-old on steroids for nephrotic syndrome who’s spending his mom’s credit card on Fortnite skins is ‘psychotic’ and not just a spoiled brat? I’ve seen kids do way worse and no one calls it psychosis. This is just medical gaslighting for lazy parents.

This is exactly the kind of clarity medicine needs. Taper first. Dose smart. Don’t assume it’s schizophrenia. Stop overmedicating. This isn’t complicated. We just need to remember: patients aren’t problems to solve - they’re people to protect. Thank you for writing this.

I had this happen to my cousin. She was on 60mg for lupus. Started screaming at her cat like it was a demon. Then she tried to flush the toilet with her phone because ‘the Wi-Fi is spying on me.’ We called the doctor. They said ‘it’s just stress.’ Two weeks later she was in psych. They tapered her and she cried for hours because she remembered what she’d done. I’m still mad.

As a medical student in India, I’ve seen this twice - both cases were misdiagnosed as bipolar disorder. One patient was on 100mg prednisone for vasculitis. He believed he was the reincarnation of Shiva and refused to eat because ‘the gods feed me ambrosia.’ We reduced steroids to 40mg. Within 72 hours, he asked for chapati and apologized. No antipsychotics needed. The fix is simple. The system is broken.

Wow - this is so well-researched. I’ve been pushing this in our hospital’s grand rounds for years. No one listens. Then last month, a 72-year-old on 80mg prednisone for polymyalgia started yelling at the ceiling. We followed your protocol - labs, taper, 5mg olanzapine IM - and she was back to knitting by day 4. I printed this out and handed it to the attending. He said ‘I’ll read it… eventually.’

It’s not about steroids. It’s about the collapse of meaning in modern medicine. We reduce complex human suffering to dosage charts and DSM codes. We forget that the body is not a machine. The psychosis? It’s the soul screaming because we stopped listening. The steroid is just the messenger. The real disease is our arrogance.

As an American veteran who served in Iraq, I find this article deeply offensive. We don’t need another liberal medical fantasy about ‘steroid psychosis.’ Back in my day, men didn’t break down because of pills - they broke down because they were weak. If your kid is acting crazy on steroids, maybe he needs a good kick in the pants and a job. Not a psychiatrist. Not a taper. Just discipline.