Gastric Ulcers from Corticosteroids: What You Really Need to Know About Prevention and Monitoring

Steroid & NSAID Risk Assessment Tool

Understanding Your Risk

Corticosteroids alone rarely cause ulcers (risk <2%), but combining them with NSAIDs increases bleeding risk by 4x or more. This tool assesses your personalized risk based on clinical evidence.

Important: PPIs are not recommended for steroid-only use. Unnecessary use increases kidney, bone, and infection risks.

Your Personalized Risk Assessment

Monitor For These Warning Signs

- Black, tarry stools (melena)

- Vomiting blood or coffee-ground material

- Unexplained fatigue or dizziness

- Persistent upper belly pain

- Unintentional weight loss

Do corticosteroids really cause stomach ulcers?

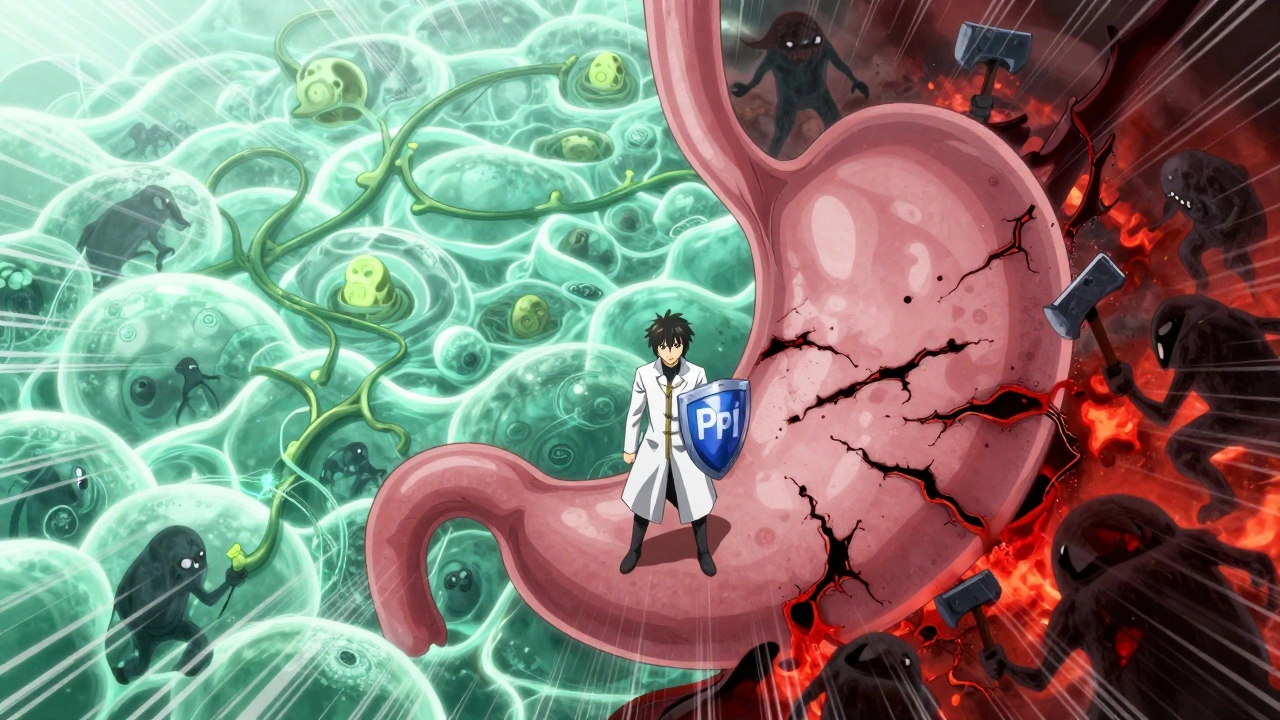

For decades, doctors have warned patients on corticosteroids like prednisone to watch out for stomach ulcers. The advice was simple: take a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) to protect your gut. But what if that advice was wrong? New evidence suggests that corticosteroids alone rarely cause ulcers - and giving PPIs to everyone on steroids might be doing more harm than good.

Let’s clear up the confusion. Corticosteroids are powerful anti-inflammatory drugs. They’re used for asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, skin conditions, and more. But they’re not magic. They come with side effects: weight gain, high blood sugar, bone loss. And for years, stomach ulcers were added to that list. The problem? The data doesn’t back it up.

A 2013 review in Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology looked at dozens of studies and found no increased risk of peptic ulcers in people taking corticosteroids alone. Even at high doses - 60mg of prednisone daily - the rate of ulcers was still under 2%. That’s lower than the rate in people taking nothing at all. So why do we still hear the warning?

The real danger: when steroids meet NSAIDs

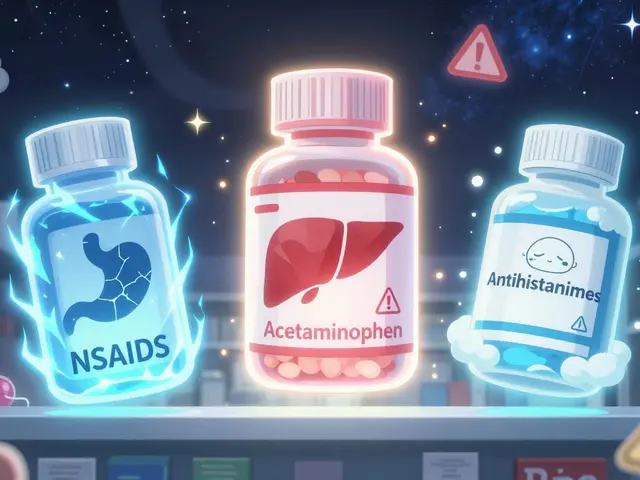

The real risk doesn’t come from steroids by themselves. It comes from combining them with NSAIDs - drugs like ibuprofen, naproxen, or aspirin. These are the painkillers most people reach for when they have a headache, back pain, or arthritis flare.

When corticosteroids and NSAIDs are taken together, the risk of a serious gastrointestinal bleed jumps by more than four times. A study of Medicaid patients showed a relative risk of 4.4 (with a confidence interval of 2 to 9.7). That’s not small. That’s dangerous.

Here’s how it works: NSAIDs block protective enzymes in the stomach lining. Corticosteroids slow down healing. Together, they create a perfect storm. One breaks down the barrier. The other stops it from fixing itself. That’s why you see ulcers, bleeding, even perforations - not from one drug, but from the combo.

If you’re on prednisone and also taking ibuprofen for joint pain, you’re in the high-risk group. That’s when you need protection - not just a PPI, but a real plan.

Who actually needs a PPI?

Not everyone. Not even most people.

A 2023 article in the Journal of Hospital Medicine titled Things We Do for No Reason™ called out routine PPI use for steroid-only patients as a practice without evidence. It’s not just opinion - it’s backed by data. At Johns Hopkins, a quality improvement project stopped giving PPIs to patients on corticosteroids alone. Over 12 months, GI complications didn’t go up. PPI use dropped by 42.7%.

At the University of Wisconsin Hospital, they launched a Steroid-Only PPI Stewardship Protocol in early 2023. They cut inappropriate PPI prescriptions by 35%. No extra ulcers. No extra bleeds.

So who should still get a PPI?

- Patients taking both corticosteroids and NSAIDs

- Those with a history of peptic ulcer or GI bleeding

- People on anticoagulants like warfarin or apixaban

- Patients with Helicobacter pylori infection (which is a major ulcer cause on its own)

- Those hospitalized and on high-dose steroids - especially if they’re critically ill

If you’re taking steroids alone, with no other risk factors, you probably don’t need a PPI. And continuing one unnecessarily exposes you to risks: kidney problems, bone fractures, low magnesium, and even C. diff infections.

What should you monitor instead?

If you’re not taking a PPI, how do you stay safe? Monitoring doesn’t mean checking for ulcers - it means watching for warning signs.

Here’s what to look for at every doctor visit:

- Black, tarry stools - this is melena, a sign of bleeding in the upper GI tract

- Vomiting blood - bright red or coffee-ground looking material

- Unexplained fatigue or dizziness - could signal anemia from slow bleeding

- Persistent upper belly pain that doesn’t go away with antacids

- Loss of appetite or weight loss without clear cause

These aren’t vague symptoms. They’re red flags. If you have any of them, you need an endoscopy - not a guess, not a pill change. An endoscopy is the only way to see if there’s an ulcer, a bleed, or something more serious.

Also, don’t forget about blood sugar. Corticosteroids spike glucose levels - especially after meals. Check your blood sugar regularly if you’re diabetic or prediabetic. Postprandial spikes are more common and more telling than fasting levels.

Why do doctors still prescribe PPIs for steroids?

Because habits are hard to break.

A 2022 survey of 347 hospitalists found that 78.3% routinely prescribed PPIs for patients on high-dose steroids - even without NSAIDs. But 63.1% admitted they didn’t have strong evidence to support it.

Doctors aren’t being careless. They’re being cautious. One patient had a massive bleed on 60mg of prednisone alone. That story sticks. It’s terrifying. It makes you want to protect everyone.

But medicine isn’t about avoiding one bad outcome at all costs. It’s about balancing risks. Giving a PPI to 100 people who don’t need it might prevent one ulcer. But it might cause 2-3 cases of kidney injury or C. diff. That’s not a win.

The shift is happening. More clinicians are asking: Do I really need to give this? The answer, more often than not, is no.

What’s next? Research is catching up

Guidelines haven’t caught up yet. The American College of Gastroenterology doesn’t have specific rules for corticosteroid-related ulcers. But that’s changing.

The American Gastroenterological Association is forming a working group to review the evidence - and their update is expected in 2025. ClinicalTrials.gov has an active study (NCT05214345) tracking GI complications in high-dose steroid users with and without PPIs. Results are due by late 2024.

Meanwhile, hospitals are leading the change. At the University of Wisconsin, they now have a checklist: Is the patient on NSAIDs? History of ulcer? On blood thinners? Hospitalized? If the answer is no to all - skip the PPI.

It’s not about ignoring risk. It’s about recognizing it correctly. Corticosteroids alone? Low risk. Steroids + NSAIDs? High risk. And that distinction changes everything.

Bottom line: Think before you swallow

If you’re on corticosteroids, here’s what to do:

- Ask your doctor: Am I taking NSAIDs? Do I have a history of ulcers or GI bleeding?

- If you’re on NSAIDs - yes, you need protection. Ask for a PPI or misoprostol.

- If you’re on steroids alone - ask if the PPI is really necessary. It might not be.

- Know the warning signs: black stools, vomiting blood, unexplained fatigue.

- Don’t assume a PPI is harmless. It’s a drug with real side effects.

Medicine is moving away from blanket prescriptions and toward smart, personalized care. Corticosteroids are powerful tools. But they’re not villains. And protecting your stomach doesn’t mean taking another pill every day - it means understanding your real risks and acting on them.

Do corticosteroids cause stomach ulcers on their own?

No, not usually. Multiple large studies, including a 2013 systematic review, show no significant increase in peptic ulcer disease in people taking corticosteroids alone. The risk is very low - around 0.4% to 1.8% - and similar to people not taking steroids. The real danger comes when steroids are combined with NSAIDs.

Should everyone on prednisone take a PPI?

No. Routine PPI use for corticosteroid monotherapy is not supported by evidence. Major hospitals like Johns Hopkins and the University of Wisconsin have stopped this practice and seen no rise in ulcers or bleeds. PPIs should only be used if you’re also taking NSAIDs, have a past ulcer, are on blood thinners, or are hospitalized.

What are the signs of a steroid-related GI bleed?

Watch for black, tarry stools (melena), vomiting blood or material that looks like coffee grounds, unexplained fatigue or dizziness (signs of anemia), sudden upper abdominal pain, or unintentional weight loss. These aren’t normal side effects - they’re emergencies. Get an endoscopy if you have any of them.

Can corticosteroids hide ulcer symptoms?

Yes. Corticosteroids reduce inflammation, which can mask pain and other typical ulcer symptoms. This means an ulcer might progress silently until it bleeds or perforates. That’s why monitoring for alarm symptoms - not relying on pain - is critical, especially in hospitalized patients.

Are there alternatives to PPIs for protecting the stomach?

Yes. Misoprostol is another option for GI protection, especially for patients who can’t take PPIs. But it has side effects like diarrhea and abdominal cramps, and it’s not safe during pregnancy. For most people, avoiding NSAIDs and managing other risk factors is the best protection. Always discuss alternatives with your doctor.

How long should I stay on a PPI if I need one?

Use the lowest dose for the shortest time possible. If you’re on steroids and NSAIDs together, consider stopping the NSAID as soon as you can. Once the NSAID is off, you can usually stop the PPI too. Long-term PPI use increases risks of kidney disease, bone fractures, and infections. Don’t stay on it longer than needed.

I've been on prednisone for years and never had an ulcer. My doctor just gave me a PPI because that's what they always do. Never questioned it until now.

This is the kind of post that makes me feel seen. So many of us are just handed pills like candy and told to swallow them without asking why. The fact that hospitals are actually cutting back and seeing no uptick in complications? That’s huge. We need more of this.

The data is clear. Steroids alone do not cause ulcers. The real issue is the conflation of risk factors. PPI overprescription is a systemic problem driven by habit not evidence.

So let me get this straight. We’ve been giving millions of people acid blockers for a decade because of a myth, and now you’re telling me the only reason we thought it worked was because we didn’t look at the actual stats? Brilliant. Just brilliant. Now can we start auditing all the other ‘standard of care’ nonsense?

The 2023 Journal of Hospital Medicine paper is cited correctly. The Johns Hopkins and UW data is solid. This isn't opinion. It's quality improvement science.

Big thanks for this. My mom’s on prednisone and I’ve been worried she’s on too many pills. This gives me actual info to talk to her doctor with. 👍

This is why American medicine is broken. You let people stop taking PPIs and then wonder why someone dies from a bleed? You’re playing Russian roulette with lives. This isn't evidence-based medicine, it's reckless.

I work in a hospital in Dublin and we’ve been doing this for a year now - no PPI unless NSAIDs or history of bleed. We’ve had zero GI events in steroid-only patients. The fear is real but the data is clearer.

The distinction between monotherapy and combination therapy is critical. The 4.4x relative risk with NSAIDs is not just statistically significant - it’s clinically devastating. This is a textbook example of risk stratification done right.

Let’s be real - PPIs are the new multivitamin. Everyone takes them because they think it’s ‘safe.’ But your stomach isn’t a garden that needs constant fertilizer. Sometimes it just needs to breathe. And yeah, C. diff is a nightmare. Don’t ignore that.

I’m from India and we’re just starting to question this. My uncle got a PPI on prednisone and ended up with kidney issues. This article saved us from another mistake. Thank you.

And to the person saying this is reckless - I get it. One bad outcome sticks. But what about the 100 people who didn’t need it? Who got kidney damage? Who got C. diff? Who had to take a pill every day for no reason? That’s the quiet harm. We’re not ignoring risk - we’re finally seeing the whole picture.