Clinical Outcomes Data: What Studies Really Show About Generic Medications for Providers

When a patient walks into your office asking why they’re now taking a generic version of their old medication, the real question behind their concern isn’t about cost-it’s about safety. Generic drugs aren’t just cheaper copies. They’re rigorously tested, FDA-approved versions of brand-name medicines that deliver the same clinical results for the vast majority of patients. But providers still hear the same worries: "Will this work the same?" "Is it safe?" "What if it doesn’t control my blood pressure like the brand did?" The data doesn’t support those fears-but understanding the evidence is key to answering them confidently.

What Does the Evidence Actually Say?

A 2019 study in PLOS Medicine looked at over 1.3 million patients across 14 different drug classes and compared outcomes between generic and brand-name versions. The results? For 12 out of 16 clinical endpoints, there was no meaningful difference in effectiveness or safety. Heart medications like amlodipine and quinapril showed identical rates of hospitalization for heart attacks or strokes. Bone drugs like alendronate performed just as well in preventing fractures. Even diabetes meds like glipizide led to the same rates of insulin initiation due to poor control. The most telling finding? In some cases, generics performed better. Patients on generic amlodipine had a 9% lower risk of cardiovascular events. Those on generic amlodipine/benazepril had a 16% lower risk. That’s not a fluke-it’s consistent with real-world data showing that when patients pay less, they’re more likely to stick with their meds. Better adherence often means better outcomes.How Are Generics Even Approved?

The FDA doesn’t just approve generics based on price. They require proof of bioequivalence. That means the generic version must deliver the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate as the brand-name drug. The standard? The concentration of the drug in the blood (measured by AUC and Cmax) must fall within 80-125% of the brand’s levels. For most drugs, that’s a wide enough range to account for normal variation between people. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, levothyroxine, or tacrolimus-the rules are stricter. The FDA uses Scaled Average Bioequivalence (SCABE), which accounts for how much the drug’s levels naturally vary in the same person over time. A 2020 study in Nature Scientific Reports followed transplant patients switching between brand and generic tacrolimus over 42 days. No clinically significant differences in blood levels or rejection rates were found. And it’s not just lab numbers. Generics must also match the brand in strength, dosage form, route of administration, and inactive ingredients (though those can differ in color or shape). The FDA reviews each generic for at least 10 months before approval. In 2022 alone, they approved 1,127 new generics.What About the Exceptions?

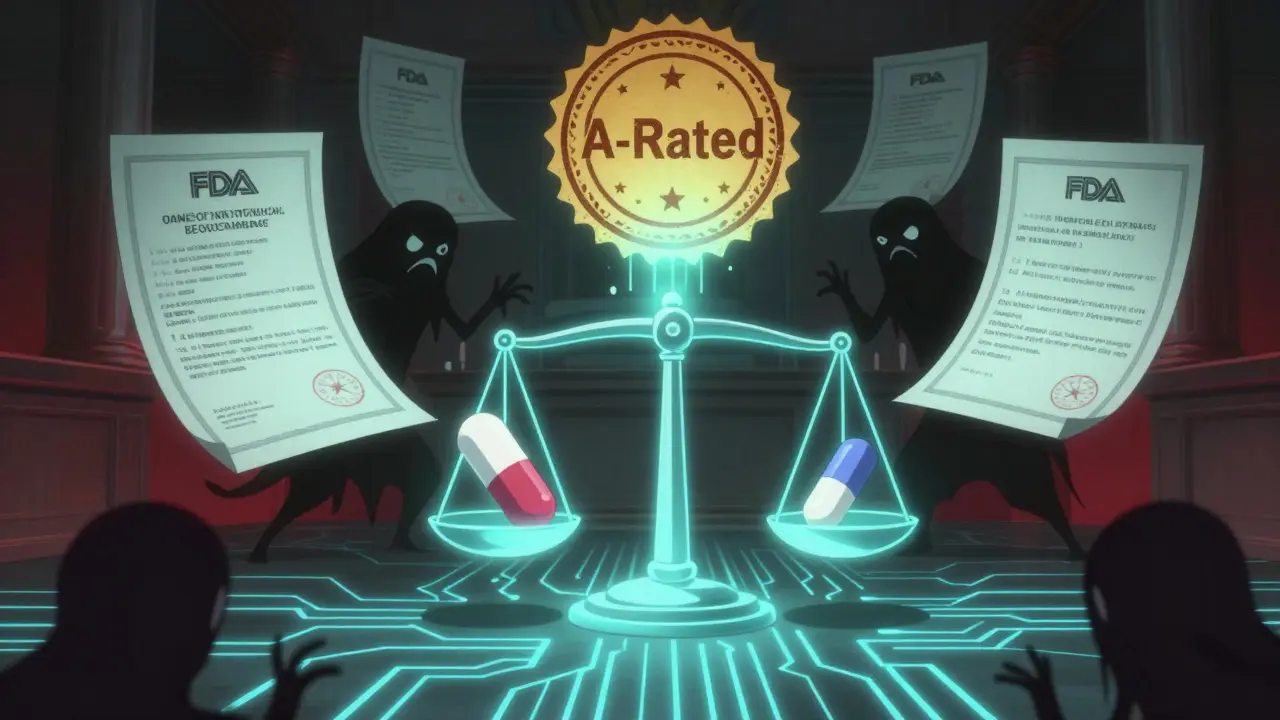

Yes, there are rare cases where patients report feeling different on a generic. But the data shows these aren’t usually about the drug itself. A 2017 FDA analysis found that patients switching from brand to generic-and then back to brand-did so at the same rate as those switching from brand to authorized generic (a brand-made version sold under a generic label). That suggests perception, not performance, drives the switch. Psychiatric medications like escitalopram and sertraline showed slightly higher hospitalization rates with generics in one study. But when researchers compared brand-name drugs to their own authorized generics, they saw the same pattern. That means the issue isn’t the generic label-it’s the change in pill appearance, packaging, or even the patient’s expectation that something changed. The FDA’s Orange Book classifies generics as "A-rated" (therapeutically equivalent) or "B-rated" (not equivalent). Over 97% of generics are A-rated. If you’re prescribing a B-rated drug, you’re likely dealing with a complex delivery system like an inhaler, topical cream, or injectable. These require extra caution, but they’re the exception, not the rule.

Why Do Patients Still Doubt Generics?

It’s not about science-it’s about psychology. Pills look different. The name on the bottle is unfamiliar. The pharmacy staff says, "This is cheaper," and suddenly the patient wonders if they’re getting second-rate care. A 2019 study found no difference in discontinuation rates between generic and brand users, but patients on generics were more likely to report side effects-simply because they expected them. The fix? Talk to patients. Don’t just say, "This is the same drug." Say: "This generic has been tested on thousands of people. The FDA requires it to work exactly like your old pill. The only difference is the price-$15 instead of $150. And the data shows it works just as well, maybe even better because you’re more likely to take it every day."What the Experts Say

Dr. Aaron Kesselheim, a leading researcher on drug policy at Harvard, reviewed 47 studies on cardiovascular drugs and found 89% showed no difference between generic and brand. He concluded: "The totality of evidence demonstrates that generic drugs are clinically equivalent to their brand-name counterparts for nearly all therapeutic classes." The American College of Physicians says physicians should routinely prescribe generics when available. The FDA states plainly: "An approved generic medicine has been shown to be bioequivalent to the brand-name medicine and is considered therapeutically equivalent." Even the Congressional Budget Office confirms it: generics saved the U.S. healthcare system $1.68 trillion between 2008 and 2017. In 2021 alone, they saved $377 billion.

What Should Providers Do?

1. Prescribe generics by default unless there’s a clear clinical reason not to. Most patients will benefit from lower cost and better adherence. 2. Check the Orange Book for A-rated vs. B-rated status. If it’s B-rated, know why-and consider whether the patient truly needs that specific formulation. 3. Address patient concerns directly. Don’t dismiss them. Explain the approval process. Show them the data. Use analogies: "It’s like buying a name-brand battery versus a store-brand one-they both power your remote the same way." 4. Monitor for rare cases. If a patient on a narrow therapeutic index drug reports a change in symptoms after switching, check levels and consider switching back-but only if clinical evidence supports it. 5. Use real-world data. Studies of millions of Medicare beneficiaries show no difference in survival rates when you adjust for health status. The initial gap? Healthier patients were more likely to get generics-not because generics were better, but because they were cheaper and more accessible.The Bigger Picture

Generics aren’t a compromise. They’re a win. For patients, they mean lower out-of-pocket costs and fewer skipped doses. For providers, they mean fewer hospitalizations and better long-term outcomes. For the system, they mean billions saved every year. The science is clear. The data is overwhelming. The only thing left to question is why we still hesitate.Are generic drugs really as effective as brand-name drugs?

Yes. For the vast majority of medications, generic drugs are clinically equivalent to their brand-name counterparts. The FDA requires them to deliver the same active ingredient at the same rate and amount, with bioequivalence tested in healthy volunteers. Large studies involving over a million patients show no meaningful differences in outcomes for heart disease, diabetes, depression, and other common conditions. In some cases, generics even lead to better results because patients are more likely to take them consistently due to lower cost.

Can switching to a generic cause side effects?

Side effects from switching are rare and usually not caused by the drug itself. Most reports of new or worsening symptoms after switching to a generic are due to psychological factors-patients expect something to change because the pill looks different or costs less. The FDA’s adverse event database shows only 0.02% of all drug-related reports involve generic-specific concerns. For narrow therapeutic index drugs like thyroid or seizure medications, occasional individual sensitivity can occur, but population-level data confirms overall safety and equivalence.

Why do some generics cost more than others?

Price differences between generics come from competition. When only one company makes a generic, it may charge more. When multiple manufacturers enter the market, prices drop quickly. Authorized generics-made by the original brand company but sold under a generic label-sometimes cost more because they’re not subject to the same competitive pressure. But they’re chemically identical to other generics. The cost difference doesn’t reflect quality or effectiveness.

Are there any drugs where generics aren’t recommended?

For most drugs, generics are recommended. The exception is the 3% of generics classified as "B-rated" in the FDA’s Orange Book-these are typically complex formulations like inhalers, topical creams, or injectables where bioequivalence is harder to prove. For these, clinicians should review the specific product and consider whether the patient’s condition requires brand-name consistency. Even then, many B-rated products still perform well in practice. Always check the Orange Book before prescribing.

Do generics have the same inactive ingredients as brand-name drugs?

No, and that’s intentional. Generic manufacturers can use different fillers, dyes, or coatings to avoid patent restrictions. These inactive ingredients don’t affect how the drug works in the body. But they can change the pill’s color, shape, or taste. Rarely, a patient may have an allergy to a specific inactive ingredient (like a dye), which is why it’s important to check the label. If a patient reports an allergic reaction, it’s worth investigating-but it’s not the active ingredient causing the issue.

How do I know if a generic is FDA-approved?

All approved generics are listed in the FDA’s Orange Book, which you can search online. Look for "A-rated" status, which means the drug is therapeutically equivalent to the brand. If a pharmacy dispenses a generic that isn’t in the Orange Book, it may not be approved or may be imported illegally. Always trust generics dispensed through licensed U.S. pharmacies-they’re held to the same quality standards as brand-name drugs.

Do generics take longer to work than brand-name drugs?

No. Bioequivalence testing ensures that generics reach the same blood concentration at the same rate as the brand-name version. If a drug is designed to work quickly (like sublingual nitroglycerin), the generic must do the same. If it’s designed for slow release (like extended-release metformin), the generic must match that profile. Studies measuring time to peak concentration (Tmax) show no clinically meaningful differences between generics and brands.

Why do some doctors still prescribe brand-name drugs?

Some doctors prescribe brand-name drugs out of habit, lack of awareness, or patient pressure. Others may be influenced by pharmaceutical marketing or misinformation. But the data doesn’t support this practice. For 97% of medications, generics are just as safe and effective. Prescribing brand-name drugs without clinical justification increases costs for patients and the system without improving outcomes. The best practice is to start with generics unless there’s a documented reason not to.

Providers who rely on clinical outcomes data don’t just make smarter prescribing decisions-they build trust. When patients understand that generics aren’t a downgrade, they’re more likely to take their meds, stick with treatment, and get better results. The evidence is there. The question is: are you ready to use it?

Generics? Please. I’ve seen guys on generics crash and burn while their brand-name buddies stayed stable. This whole ‘FDA says it’s fine’ thing is just corporate propaganda. They don’t care about you, only profits. If it was truly the same, why do pharmacies push them so hard? Something’s off.

It’s not about the pill. It’s about control. We’ve been conditioned to equate price with value. A $15 pill feels like a discount bin medicine-even if it’s chemically identical. The real crisis isn’t pharmacology, it’s our collective psychological dependence on branding. We need to outgrow this.

This is exactly why I love science. No drama, just data. Generics save lives by making treatment possible for people who otherwise skip doses. Simple as that.

In my country, generics are the only option. People live longer with them. The science is clear. What matters is access-not the label on the bottle. Let’s stop fearing what works.

bro i switched to generic lexapro and my anxiety went nuts 😭 like i swear it was the pill not my brain. why does this happen??

There’s a deeper layer here that rarely gets discussed. The placebo effect isn’t just about expectation-it’s about identity. When you’ve been on a brand-name drug for years, it becomes part of your story. The pill is a symbol of stability. Switching to a generic doesn’t just change the chemical composition-it changes your narrative. That’s why some people feel worse. It’s not the drug. It’s the loss of ritual. The color, the shape, the name-they’re anchors. When you take those away, even if the science says it’s identical, the psyche rebels. We’re not just biological machines. We’re meaning-making creatures. And meaning doesn’t always follow bioequivalence curves.

Prescribe generics. Save money. Save lives. End of story. Stop overthinking it. People need meds not excuses

My grandma’s on generic blood pressure med and she’s been rock solid for 3 years. She doesn’t even know the difference and she’s doing better than most people i know. Sometimes the simplest answer is the right one 🤗

Let’s be brutally honest: the FDA’s bioequivalence standard of 80-125% is a joke. That’s a 45% variance. If your blood pressure med fluctuates that much, you’re playing Russian roulette. And the fact that they approve 1,127 generics a year without long-term outcome studies? That’s not regulation-it’s negligence dressed in lab coats.

They’re lying. All of them. Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know that generics are made in China in factories with rats in the walls. My cousin’s uncle’s neighbor took a generic and his liver exploded. You think that’s a coincidence? Wake up. This isn’t medicine-it’s a control system.

Same drug. Same result. Stop overcomplicating.

Why do all the generics have the same weird blue color? Coincidence? Or are they using the same cheap dye to track us? I’ve seen this pattern since 2016. They’re not just saving money-they’re monitoring us.

i switched to generic omeprazole and my stomach started acting up. i thought it was stress but then i read a blog that said the fillers in generics cause inflammation?? idk man. i went back to prilosec and now i’m fine. maybe the system is rigged?