How Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Affects the Cardiovascular System

COPD Cardiovascular Risk Calculator

Assess Your Cardiac Risk

This tool estimates cardiovascular risk based on COPD severity and key clinical indicators. Results help identify early signs of heart involvement.

Results

Quick Takeaways

- Obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) raises the risk of heart failure by 30‑40%.

- Poor oxygen levels trigger pulmonary hypertension, which strains the right ventricle.

- Systemic inflammation from COPD accelerates atherosclerosis and left‑side heart disease.

- Early detection of cardiac changes can improve survival and quality of life.

- Targeted therapies - smoking cessation, inhalers, statins, rehab - lower cardiovascular events.

What is Obstructive Pulmonary Disease?

When it comes to chronic lung conditions, Obstructive Pulmonary Disease is a group of disorders that block airflow and make breathing tough. The most common form is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which combines emphysema and chronic bronchitis. Global data from the WHO in 2023 shows over 250million people live with COPD, and mortality has risen 15% in the last decade.

Key attributes of COPD include persistent cough, sputum production, and a reduced forced expiratory volume (FEV1). The disease progresses in stages-GOLD1 (mild) to GOLD4 (very severe)-based on spirometry readings. While the lungs bear the brunt, the heart feels the squeeze, too.

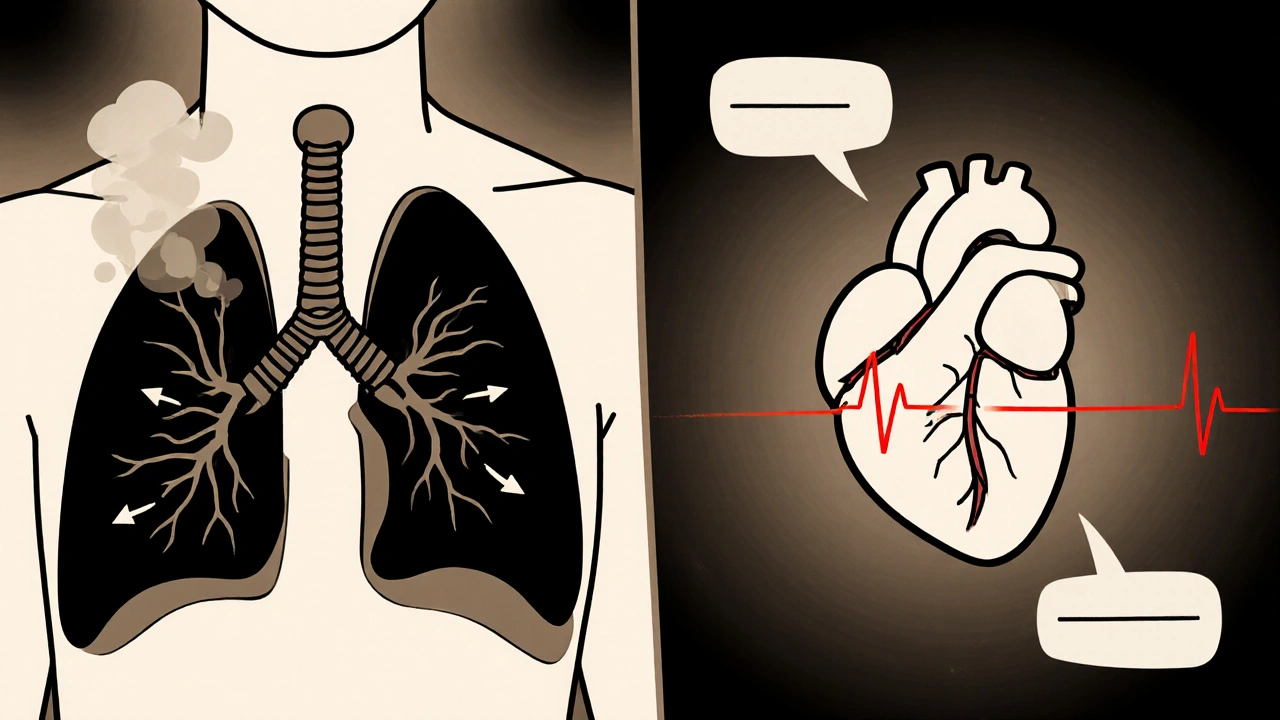

Why the Heart Pays the Price

The heart and lungs share a tight partnership: the lungs oxygenate blood, the heart pumps it. Disrupt one side, and the other compensates-often at a cost.

Three major pathways link COPD to cardiovascular trouble:

- Hypoxemia-low oxygen in the blood-forces the pulmonary arteries to constrict, raising pressure.

- Systemic inflammation-the chronic release of cytokines-spreads beyond the lungs and harms blood vessels.

- Oxidative stress-free radicals from smoke and inflamed tissue-promote atherosclerotic plaque build‑up.

Each pathway can be traced back to specific entities that we’ll unpack next.

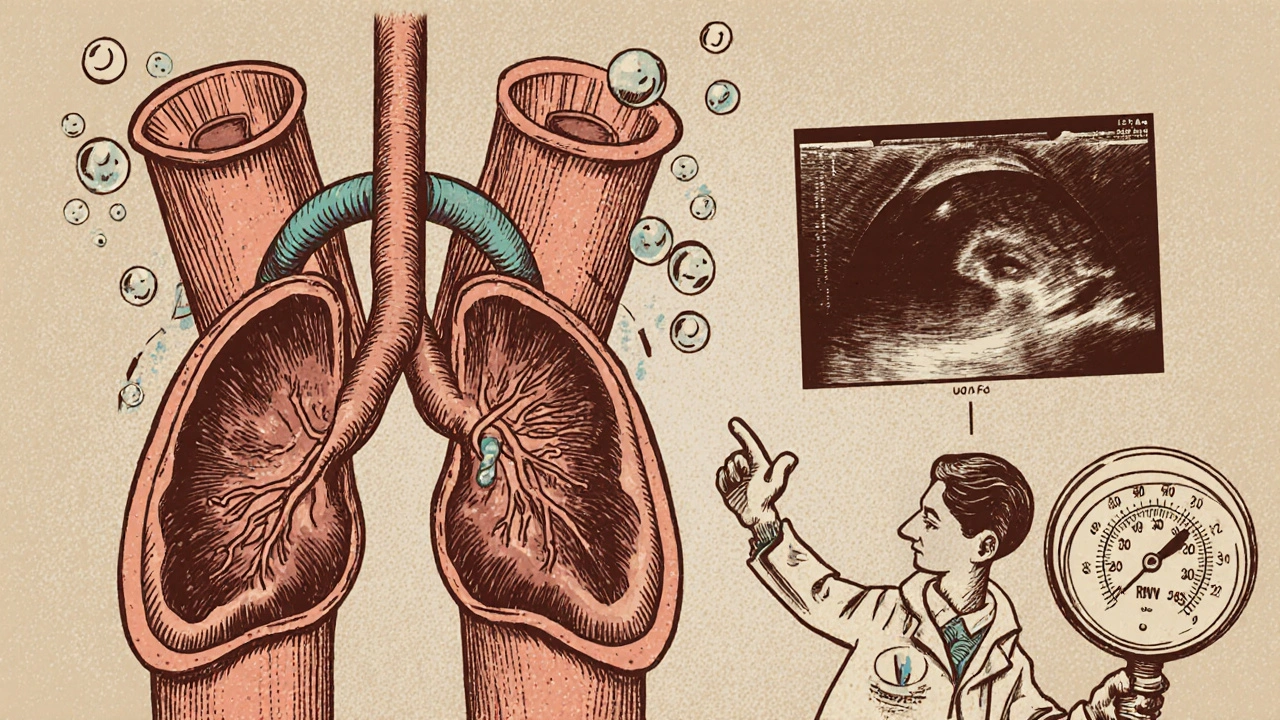

Pulmonary Hypertension and the Right Ventricle

Low oxygen triggers the pulmonary arteries to narrow, a condition known as hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Over months, the pressure climbs, and the condition is labeled pulmonary hypertension. Studies from the European Respiratory Journal (2024) report that 25‑30% of severe COPD patients develop pulmonary hypertension.

The right ventricle (RV) is a thin‑walled pump designed for low‑pressure flow. When faced with high pulmonary pressures, it thickens (right ventricular hypertrophy) and eventually fails-right‑sided heart failure. Symptoms include peripheral edema, jugular vein distension, and a characteristic “pulsatile liver.”

Impact on Left Ventricular Function and Atherosclerosis

Systemic inflammation in COPD raises levels of C‑reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin‑6 (IL‑6). These markers are also key drivers of atherosclerosis. A 2022 meta‑analysis of 18 cohort studies found that COPD patients have a 1.5‑fold higher risk of coronary artery disease.

Oxidative stress from smoking and chronic airway inflammation damages endothelial cells, leading to plaque formation. When plaques become unstable, they can rupture and cause myocardial infarction.

Additionally, hypoxemia stimulates sympathetic nervous system activity, raising heart rate and blood pressure-both risk factors for left‑ventricular hypertrophy.

Key Clinical Signs Your Doctor Should Watch For

Because COPD symptoms often mask cardiac problems, clinicians use a combination of clues:

- Disproportionate breathlessness compared to spirometry results.

- Elevated BNP (B‑type natriuretic peptide) indicating cardiac strain.

- ECG changes: right‑axis deviation, P‑pulmonale, or occasional ST‑T abnormalities.

- Echocardiography revealing RV enlargement or pulmonary artery systolic pressure >35mmHg.

- Six‑minute walk test showing early desaturation (<88%) and reduced distance.

Early detection allows for targeted interventions before full‑blown heart failure sets in.

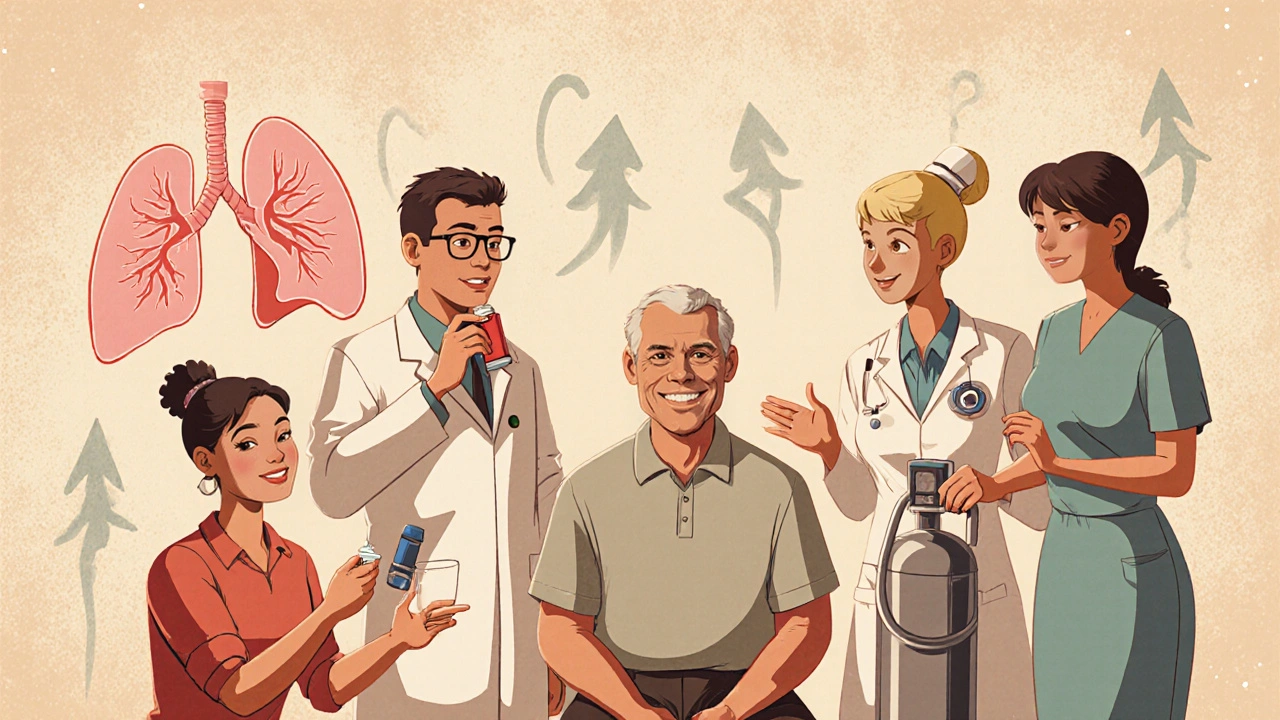

Managing Cardiovascular Risk in COPD Patients

Treatment must hit both lungs and heart.

- Smoking cessation: The single most effective step. Within a year, CRP drops by 30% and arterial stiffness improves.

- Bronchodilator therapy: Long‑acting β2‑agonists (LABA) and anticholinergics reduce hyperinflation, lowering intrathoracic pressure on the heart.

- Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS): When combined with LABA, they blunt airway inflammation, indirectly dampening systemic cytokine spill‑over.

- Statins: Evidence from the IMPACT trial (2023) shows statins cut major cardiovascular events in COPD by 22% even in patients without baseline hyperlipidemia.

- Pulmonary rehabilitation: Structured exercise improves VO₂ max, reduces sympathetic drive, and strengthens the RV.

- Oxygen therapy: Long‑term nocturnal O₂ in patients with PaO₂<55mmHg slows pulmonary hypertension progression.

Management should be individualized, but a multidisciplinary approach-pulmonology, cardiology, physiotherapy-yields the best outcomes.

Comparison of Cardiovascular Impact: COPD vs. Asthma

| Risk Factor | COPD | Asthma |

|---|---|---|

| Incidence of Pulmonary Hypertension | 25‑30% | 5‑7% |

| Right‑Heart Failure Rate | 12‑15% | 2‑3% |

| Elevated CRP (>3mg/L) | 68% | 22% |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 1.5× higher vs. non‑COPD | 0.9× (no increased risk) |

| All‑cause Mortality (5‑yr) | 28% | 12% |

The table highlights why COPD patients need vigilant cardiac surveillance, while asthma, though inflammatory, generally spares the heart.

Take‑Home Message

Obstructive pulmonary disease does more than steal breath-it puts a heavy load on the heart. By recognizing hypoxemia‑driven pulmonary hypertension, systemic inflammation, and oxidative stress, clinicians can intervene early. Combining lung‑focused therapies with cardiovascular risk‑reduction strategies cuts deaths and improves daily function.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can COPD cause a heart attack?

Yes. The chronic inflammation and oxidative stress seen in COPD accelerate atherosclerosis, raising the odds of a myocardial infarction by about 1.5 times compared to non‑COPD smokers.

Is pulmonary hypertension always present in severe COPD?

Not in every case, but studies show roughly a quarter of patients with GOLD3‑4 COPD develop pulmonary hypertension. Regular echocardiograms help catch it early.

Do inhaled steroids protect the heart?

Inhaled corticosteroids reduce airway inflammation, which modestly lowers systemic cytokine levels. While they’re not a primary heart‑protective drug, they contribute to overall risk reduction when used appropriately.

Should every COPD patient get a statin?

Current guidelines recommend statins for COPD patients with existing cardiovascular disease or traditional risk factors. For those without, a shared decision‑making approach-considering age, lipid levels, and inflammation markers-is advised.

How often should cardiac screening be done for COPD?

A baseline echocardiogram at diagnosis of moderate‑to‑severe COPD is wise. If symptoms evolve-worsening dyspnea, edema, or elevated BNP-repeat imaging within 6‑12months.

The government and Big Pharma are hiding the real cure for COPD‑related heart failure!

In many cultures, breathing exercises are passed down through generations and can complement modern COPD treatment.

When patients incorporate those traditions, they often report better endurance during daily activities.

Encouraging clinicians to respect and integrate such practices can improve adherence and outcomes.

It is a most splendid irony that a disease of the lungs should so elegantly drape its toxic veil over the heart, wouldn’t you agree?

One might posit that the tangled web of systemic inflammation is merely the body’s melodramatic attempt at self‑destruction, a theatrical performance played out on the vascular stage.

The hypoxic cascade, indeed, whispers sweet nothings to the sympathetic nervous system, coaxing it into a perpetual state of over‑drive.

Consequently, arterial pressure climbs as if scaling an insurmountable cliff, while the coronary arteries lament their fate.

One cannot overlook the relentless onslaught of oxidative stress, which, like a mischievous imp, assaults endothelial integrity at every turn.

When the endothelial barrier yields, atherosclerotic plaques take center stage, growing in size and, inevitably, in menace.

This process, dear readers, is accelerated by the very cytokines that the lungs cough out in a perpetual chorus of inflammation.

Furthermore, the right ventricle, originally designed for gentle breezes, is now forced to labor against a torrent of elevated pulmonary pressures.

Its hypertrophic response is but a futile attempt to maintain output, reminiscent of a pianist playing an increasingly complex sonata on broken keys.

Ultimately, the heart capitulates, and right‑sided failure manifests with the elegance of a tragic heroine.

Picture the lungs and heart as dance partners in a vibrant, kaleidoscopic ballroom; when the lungs miss a step, the heart swoops in trying to keep the rhythm.

Their tango becomes a jittery jitterbug, especially when inflammation throws confetti everywhere.

Keeping the beat steady with rehab and medication can restore some grace.

Ah, the melodrama of a failing organ-how delightfully predictable!

Let’s just say the plot twists are as stale as yesterday’s toast.

While the prevailing narrative glorifies a linear hypoxia‑inflammation‑cardiovascular axis, one must interrogate the latent variables obscured by methodological myopia.

The interplay of neurohumoral feedback loops and endothelial shear stress introduces a stochastic element that defies simplistic causality.

Thus, any monolithic therapeutic approach risks being reductively myopic.

Indeed, the integration of pulmonary and cardiac biomarkers, such as BNP and CRP, offers a multidimensional perspective, facilitating nuanced patient stratification,

which, in turn, enables targeted interventions; however, the clinical implementation remains hampered by systemic constraints, resource allocation, and interdisciplinary communication gaps,

necessitating a concerted effort to align research protocols with pragmatic care pathways.

Indeed, collaborative care makes a big difference.

One could argue that the cardiovascular sequelae of COPD are merely an inevitable corollary of chronic hypoxemia, yet the literature suggests otherwise, weaving a tapestry of inflammatory mediators and oxidative insults that conspire against vascular integrity.

Moreover, patient adherence to inhaled therapy can pivotally alter the trajectory of right‑ventricular remodeling, a fact often underemphasized in mainstream discourse.

Nevertheless, the heterogeneity of disease phenotypes demands individualized assessment, lest we succumb to a one‑size‑fits‑all paradigm.

In practice, integrating six‑minute walk desaturation metrics with echocardiographic surveillance yields a richer diagnostic canvas.

Thus, a multidisciplinary approach is not merely advisable-it is indispensable.

Don't you see? The pharma giants 👽 are using COPD as a Trojan horse to pump us with profit‑driven meds 😡💊.

Well, another day, another half‑baked review that tries to sound profound while saying basically nothing.

Looks like someone spent more time picking font colors than reading the actual studies.

Hey there! 😊 If you’re looking to track early cardiac changes, consider adding routine BNP checks and a quick echocardiogram during COPD follow‑ups. It really helps catch right‑ventricular strain before it escalates! 🌟

Let’s cut the fluff-addressing systemic inflammation head‑on with statins and pulmonary rehab isn’t optional, it’s a must.

Patients who ignore this integrated strategy are essentially signing their own discharge papers.